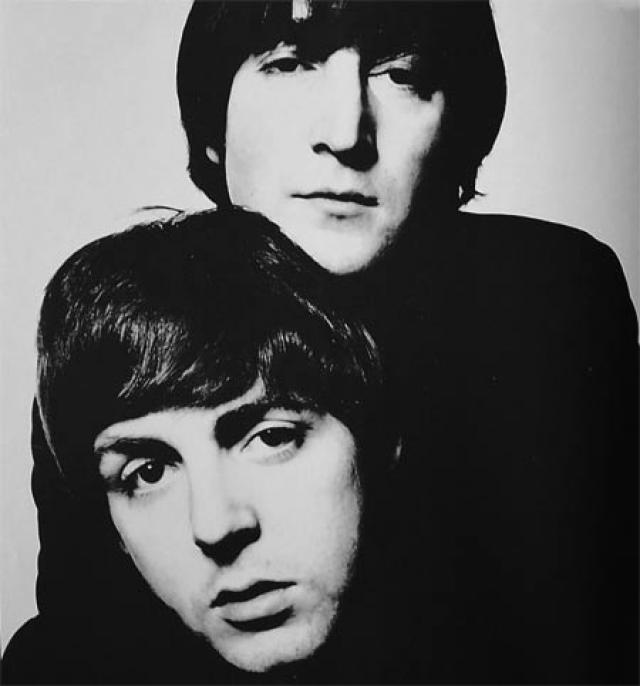

Lennon and McCartney, Buffett and Munger, Jobs and Wozniak, Watson and Crick—how creative pairs come together and create together and why greatness so often arrives in two’s.

Lennon and McCartney, Buffett and Munger, Jobs and Wozniak, Watson and Crick—how creative pairs come together and create together and why greatness so often arrives in two’s.

We have long been under the influence of the myth of the lone genius that toils in isolation and one day emerges with the brilliant creation. But if you dig deeper, you’ll find that a great achievement—the groundbreaking scientific discovery, work of art or technological breakthrough—is often the result of two individuals who come together as a pair to form a joint creative identity.

In his new fascinating and meticulously researched book, the Powers of Two, Josh Wolf Shenk writes about dozens of creative dyads. Shenk’s analysis of the inner workings of some of the world’s most famous creative pairs—why some work and others don’t and why some that once worked, break apart—is a goldmine of information for any two people wanting to become the next John and Paul or Jobs and Woz.

Even though he spent six years writing and researching his book, Shenk told us, he’s been astounded to find that the creative dyad phenomenon is even more widespread than he thought. “Ever since the book came out, people have been contacting me with stories of famous collaborators,” he said, “when all along I had thought it been just been the one guy.”

Here are Shenk’s four steps of the creative dyad life cycle:

Why you have to be the same…but different

Two people meet and there is a spark because they share an intense love of the same thing. But why work together if you don’t bring different things to the table? It was a late November afternoon in 1962 when John Lennon and Paul McCartney got together at Paul’s father’s house in Liverpool to write a song for their debut album, Please Please Me. They sat facing each other, playing their guitars (“like mirrors,” Paul said) with a lyric-filled notebook between them. McCartney had a new song he’d started. He played the opening for Lennon: She was just seventeen/Never been a beauty queen. John snorted, “You’re joking about that line, aren’t you?” Paul copped to it being bad. After batting around ideas, John put a suggestive spin on the lyric: She was just seventeen/You know what I mean. “They had joined sin to innocence,” writes Shenk, “taken a promising image and given it a lusty, poetic kick.”

What draws two creative individuals together is not just their similarities, but their differences. In the case of Lennon and McCartney, they loved the same music, American rock n’ roll. But just as important were their divergent influences. What made the Beatles the Beatles was McCartney’s poppy sing-alongs and bright paeans to love, married with Lennon’s bluesy, introspective, self-explorations.

“Obviously, any two people differ from each other in some ways and resemble each other in others, but in potent pairs,” writes Shenk, “it’s taken to an uncanny extreme….”

How two people form a joint identity

Making a connection with someone through work can be the creative equivalent of love at first sight. But the movement to true partnership, like a strong marriage, is often slow and meandering. “It’s the gestational phase that has to happen in order for the creative work to really take off,” Shenk told us.

Take Charlie Munger and Warren Buffet. Introduced by a mutual friend in 1959, Munger and Buffet lived in different cities, worked in different businesses (Munger in real estate law, Buffet in finance) and had different investing philosophies. In regular phones calls and occasional visits, Munger and Buffett exchanged ideas and advice. Munger learned from Buffett about buying companies with investor capital. Buffett learned from Munger that bargain hunting often made less sense than paying a reasonable price for a good company.

Over the next couple of decades the pair developed confidence and trust in each other by talking every morning on the phone and investing in some of the same deals. They created what psychologists call a “joint identity.”

It wasn’t until nearly twenty-five years after their first meeting that they finally formalized their partnership when Munger took a stake, and the vice chairman position, in Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway. And both have acknowledged that their partnership built on mutual respect and speaking the truth has been crucial to the Buffett/Munger juggernaut.

When the sum is greater than the parts

There’s the star and the director, the inventor and the salesman, the dreamer and the doer “In the heart of their creative work, pairs thrive on distinct and enmeshed roles, taking up positions in archetypal combinations…,” writes Shenk.

Steve Jobs and Stephen Wozniak embodied that dynamic. The pair met through a mutual friend as young adults, and “just sat on the sidewalk for the longest time…sharing stories.”

Woz, the engineer, said his success with Jobs was due to “my engineering skills and his vision.” In this way, Wozniak clearly labeled himself the doer and Jobs the visionary. “And that’s how Woz elected to remain, an engineer at the periphery of Apple’s organizational chart, free from the responsibilities of managing the business or other people,” Shenk tells us. Meanwhile, Jobs who could not have built a PC on his own chose the spotlight. Shenk adds, “Over the next thirty-four years Jobs became arguably the most recognized visionary in the computer industry.”

What a pair?! It was “Woz who conceptualized a powerful new technology, and Jobs…who recognized the potential of the idea and then shaped, refined and marketed it,” Shenk writes. Without Jobs we probably never would have heard of Woz. And without Woz there probably would be no Apple.

When things fall apart

In the late 1950’s two ambitious and brainy scientists met every day for lunch at the Eagle Pub in Cambridge, England. When James Watson and Francis Crick went back to work, their conversation continued. Their chatter in the lab was so incessant, that other scientists complained. The pair’s punishment? A shared office. This led to the pair’s groundbreaking discovery (in just 18 months) of the structure of DNA and a Nobel Prize.

Watson and Crick were nothing if not candid with one another always shooting down one another’s ideas freely. The death knell to real collaboration, Crick once said, is “politeness.” But after their discovery, it turned out that what the two scientists had admired in each other—their mutual ambition and candor—drove them apart. They never worked together again.

Fifty plus years after the discovery when Shenk asked Watson why, Watson replied: “You couldn’t be with Francis and be the boss. Whereas I enjoy being the boss.”

Who knows what other genius creations could have come from the shared minds of Watson and Crick, Lennon and McCartney or other dynamic duos that dissolved? One key to making a creative partnership work may just be knowing what makes a creative partnership work… and what doesn’t.

Order “The Art of Doing” here. Signup for “The Art of Doing” free weekly e-newsletter. Follow us on Twitter. Join “The Art of Doing” Facebook Community. If you’ve read “The Art of Doing” please take a moment to leave a review here.